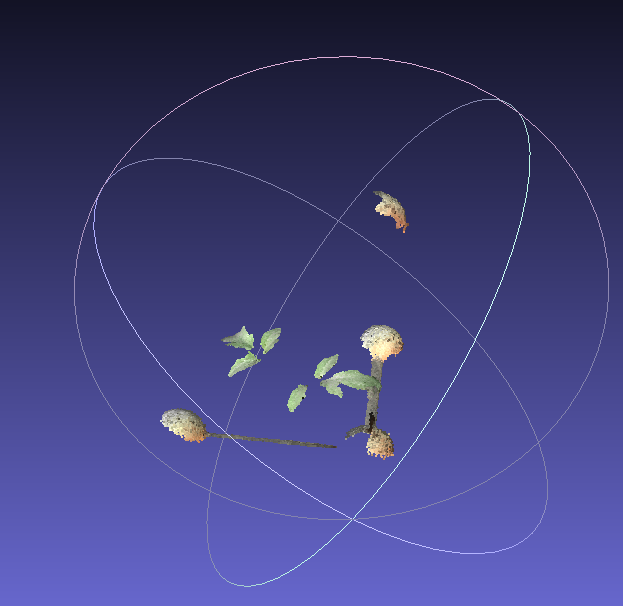

This week was spent mostly on scanning the tomato plants. The previous scans look nice in the visualization, but there is a lot to do before the computer simulation can use that data. First, we have to get the proper orientation. The scanner guesses at a random coordinate system origin and orientation. The scale is right, but the computer needs to know which way is up. The system I developed is to make a small model with spheres to scan with the plant. This is attached to a wooden frame that I can screw into the same holes in the growth chamber every time I do a scan. Every scan has this model included and it’s in the same orientation every time.

Using the program Cloud Compare, I can then make a virtual model, which pretty simple, just 4 spheres. By clicking on the scan of each model sphere, and the corresponding virtual model sphere, the computer reorients the plant to match the orientation of my virtual model. This sadly requires some human input, but I think that’s kind of inevitable.

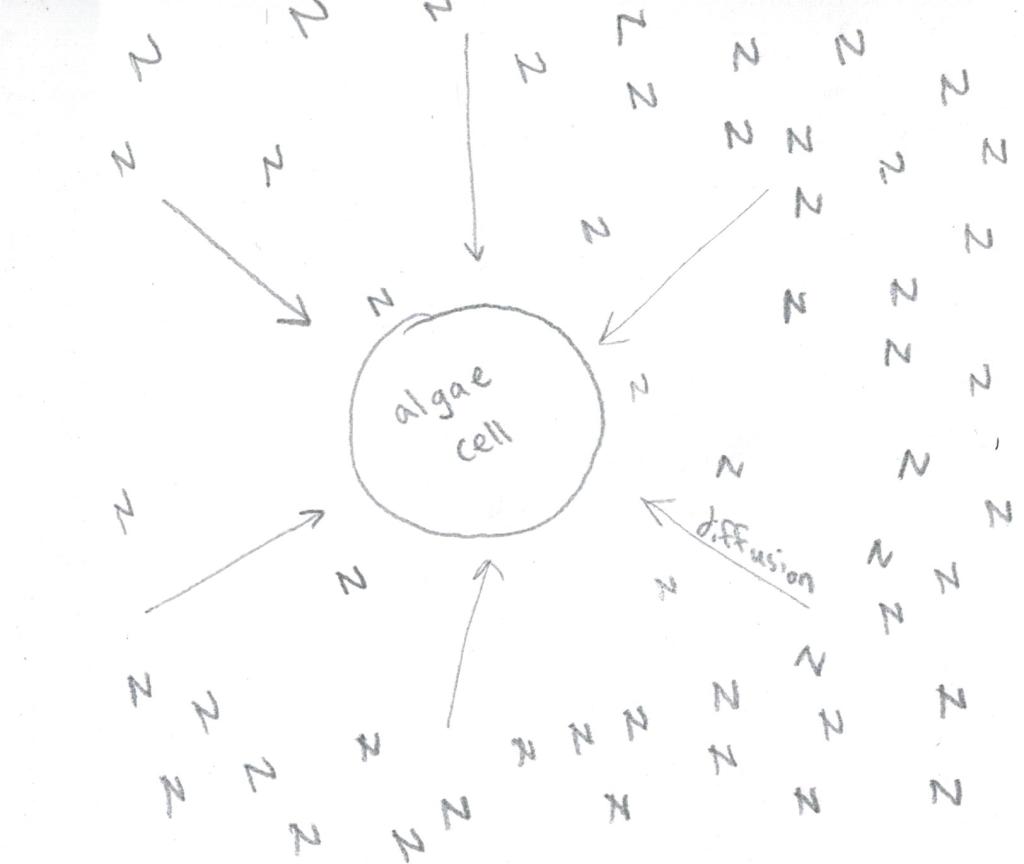

Once the model is oriented, I save it and run a python script that removes the model. I had a bunch of trouble with this, but then I realized that my orange model and green plants were too close to the same color. By painting the model magenta, which reflects only red and blue light I could use the color to extract only the green scan points, which are the plant leaves. Next, the scan is converted to a mesh of triangles and saved as a .stl file. Then the area of the leaves is easy to measure in my ray tracer program. This part is all automated, and I can set the computer to do a bunch of files at once. The only problem is that the python parts are really slow. If it becomes an issue as the plants get bigger I may have to put this all into c++. But for now I’m not in a hurry, it’s only a few minutes per plant.

The data is somewhat dependent on operator technique, the scanner in hand held and sometimes I miss a leaf. I scanned every plant twice and leaf area results were within 10%, so I think that’s probably good enough, and my technique may improve. Another issue was getting the sphere model in the scan. The plants scan very nicely, they have a lot of texture for the scanner to track. The model is perhaps too smooth. I will add some small magenta “leaves” on it, and use a smaller model that’s easier to keep in the field of view with the plant for future scans.

My water manometer did not work as intended… When the pressure differential returned to zero, the water difference would not quite go back to zero. I’m still not quite sure what I did wrong, but I rebuilt it with larger tube and used canola oil as the fluid and it’s fine now. So lower surface tension perhaps? Anyhow, apart from adjusting for the density of canola oil vs water this is preferable since it won’t freeze below 0c. My blower can maintain 20 mmH2O (millimetres of water column) with speed control on max, so I can experiment with pressure in the double layer greenhouse glazing.